The Infinite Money Glitch and Its Effects

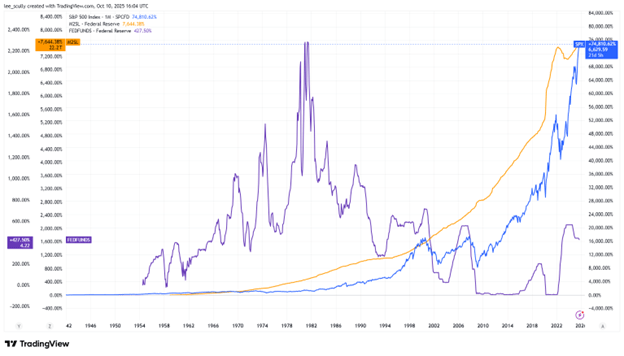

Take a look at this chart from the early 1940s to today.

Blue: S&P 500 index (a proxy for the U.S. stock market)

Orange: M2 U.S. Money Supply (a proxy for the amount of USD circulating in the financial system)

Purple: Federal Funds Rate (a proxy for U.S. monetary policy and interest rate levels)

What do you notice?

What does that mean?

It means that "investors" have been paying astronomical prices for stocks (and most financial assets), especially over the past two decades, because there is so much cheap cash in the system with which to “invest.”

"Investors" seem to have forgotten that returns are a direct function of the price paid.

Higher price paid = lower return expected, ceteris paribus.

When the system is flush with ever-increasing cash at historically low borrowing costs (interest rates), it has the effect of gamifying the market and dislocating the prices of assets from their true value. The term “casino” has been used to describe the market recently. This dynamic has proliferated over decades and caught steam over the past 15 years, since the Ben Bernanke era of the U.S. Federal Reserve (central bank).

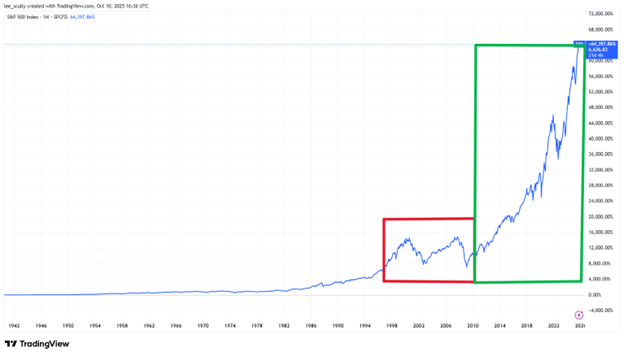

Bernanke’s policies were defined by aggressive, experimental monetary actions designed to prevent financial collapse and sustain recovery in the aftermath of ’08-09.

In a normal economic cycle, there are booms and busts. Bernanke’s policies prolonged the bust, which still hasn’t happened yet – 17 years and counting without a meaningful or sustained stock market correction.

Had he allowed the natural market cycle to run its course, we might have expected to see a cycle akin in magnitude to the dot-com era and the lead-up to the global financial crisis (red box). Instead, these monetary interventions have altered the cycle entirely. They have created what we believe to be the greatest financial market bubble in history (green box):

This explains why “value investing” has taken a backseat, as has active investing:

1. How can anyone buy a stock for less than what it’s intrinsically worth (the core principle behind value investing) when prices for most stocks no longer respect intrinsic values?

2. Why would anyone pay a money manager to tactically move in and out of specific stocks when they could buy the market, do nothing else, and perform just as well, if not better, without paying management fees? If everything goes up all the time, where’s the value in active management?

Those are the questions that the chart above should provoke.

We believe the answers could be:

1. In most cases, we can’t successfully employ a value strategy. Value investing isn’t working anymore and hasn’t for some time. The market has favoured growth investing.

There are few traditional value opportunities in the market. This explains why Warren Buffett, the most famous value investor of all time, is currently heavily overweight cash – because there are few investments in which to place that cash at a price near or below the true value of the investment.

2. “Mom-and-pop” investors wouldn’t pay a money manager if their main concern is “how much money can I make?” But they most certainly will, if their main concern is “how much money can I lose?”

The most successful investors in history are those who have shared the latter attitude.

Many investors don’t care about the price they pay anymore. Everything seems to go up all the time. That’s been the case for the last 17 years, mostly.

Most have lost sight of the need for risk management in the pursuit of returns. That complacency can, and likely will, prove detrimental. As renowned economic thinker John Hussman says:

“A market collapse is nothing but risk-aversion meeting a market that’s not priced for risk.”

This means that when the party ends, it will likely end abruptly.

Things often “take the stairs up and the elevator down.” It’s been a long climb up the stairs; what will the elevator ride look like?

The value in active, tactical investment management is in seeking appropriate risk-adjusted returns. Recall that an investment that loses 50% of its value must then earn a return of 100% in order to just break even.

The fact that the market is more overvalued than it has ever been in recorded history, does not mean that respectable risk-adjusted returns cannot be made. It means that investors should be prudent in the strategies they employ to earn such returns. Buying and holding the broader market has been a successful strategy, but it turns a blind eye to risk.

How much further can the market climb? Nobody knows. Will it go up forever? Nobody knows. An educated guess that takes hundreds of years of history into account and zooms out to see the big picture, is that, no, it will not go up forever. Things have always changed throughout history and we expect change to continue being a constant.

Raymond James (USA) Ltd. advisors may only conduct business with residents of the states and/or jurisdictions in which they are properly registered. Raymond James (USA) Ltd. is a member of FINRA / SIPC.

Information in this article is from sources believed to be reliable, however, we cannot represent that it is accurate or complete. It is provided as a general source of information and should not be considered personal investment advice or solicitation to buy or sell securities. The views are those of the author, Lee Scully, and not necessarily those of Raymond James Ltd. Investors considering any investment should consult with their Investment Advisor to ensure that it is suitable for the investor’s circumstances and risk tolerance before making any investment decision. Raymond James Ltd. is a Member Canadian Investor Protection Fund.